Wurzer family

The Wurzer family (f.k.a. der Wurzer von Wurz) was an old Upper Palatinate noble family. The family belonged to the uradel in the Nordgau and first appeared in the 11th century as imperial servants (reichministeriales) of the Holy Roman Emperor. The earliest reference to the family is from an imperial register in 1069 AD, which mentions the ancestral estate of Wrzaha (the modern-day village of Wurz near Neustadt an der Waldnaab). The first known ancestor was Cunradus de Wourz, the ministeriale (dienstmann) documented in 1219 AD. As early as the 13th century, the family served as knights (milites), ministeriales, and castellans (burgmanner) to the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg.[2]: 14 By the end of the 15th century, the main branch of the family went extinct, and most of the family’s land holdings and wealth transferred to the Mendel von Steinfels through marriage. Around the same time, the other branches of the family began to experience financial and legal difficulties, and began to recede into the landed gentry. Beginning in the 16th century up until the present, their descendants can be found in the house books (hauserbucher) of Helmut Reis and also in the Regensburg diocese baptismal records. Here they are recorded as farmers, still living in the villages in and around Wurz, more than 950 years after the first mention of the estate.

History

[edit]Origin and variants of the name

[edit]

Little is known about the early history of the Wurzer (von Wurz) family prior to the 13th century (see Siebmacher's Wappenbuch, "a little known family"[1]). The family appears to have originally resided in Lower Bavaria but eventually migrated north into the uncultivated frontiers of the Nordgau. This move likely came at the behest of the bishopric in order to take part in forest clearing and in the Christianization of the Slavic settlers.

After migrating into the Nordgau, the family settled at Wurz near Neustadt an der Waldnaab, which would become their eponymous ancestral seat. According to local chronicler Christoph Schulze, the estate of Wurz is first mentioned as the fortified settlement Wrzaha in an imperial document in 1069 AD. In this document, King Heinrich IV hands over the praedium of Wrzaha, in his margraviate in the Nortgowe district (Nordgau), to Bishop Hermann of Bamberg and his church.[3] While there are no remnants of the medieval fortification, there exists a ring-shaped structure on a hill east of Wurz, called the Loherl, that may have been part of the original Celtic oppidum upon which the later fortification may have been built.[2]: 17

One theory states that the place name Wrzaha is derived from the word compound ‘Dvur’ (Slavic for hof) + ‘Drozza’ in reference to the ministeriale Drozza family. According to this theory, the von Wurz family were descendants of the earlier Drozza (Babenberg) clan who settled around Bamberg. The Drozza were one of the five original Bavarian noble families which are mentioned in the Lex Baiuvariorum in the 8th century.[2]: 21 Over time, the difficult to pronounce Dvur Drozza was Germanicized as Wrzaha. Eventually, Wrzaha was shortened to its current form of Wurz.

The spelling of the family name continually changed and evolved throughout the 12th-16th centuries: de Wourz, de Wrtz, de Wurz, von Wurz, von Wurtz, der Wurzer von Wurz, Wurtzer, Wurczer, Wurzzer, Wurzer. As is customary with nobiliary particles, the initial use of the Latin ‘de’, and later the German ‘von’ (meaning ‘of’), preceded the place of origin (i.e., von Wurz). Later the ancestral name became fixed (i.e., der Wurzer, meaning ‘the Wurzer’ or ‘the ones from Wurz’). In the 1300s, as family members were granted fiefs outside of Wurz, the place of origin was followed by the current place of residence (i.e., der Wurzer zu Kaimling, der Wurzer zu Kemaden, der Wurzer zu Ruprechtsreut, der Wurzer zum Stornstein). In the mid-1400s, the family were no longer counted among the nobility and the 'von' and 'zu' were eventually dropped. By the 1500s, ‘true’ surnames became commonplace throughout what is now Germany and the family name was simplified as Wurtzer or Wurzer.

Imperial affiliations

[edit]From the 11th to the 13th centuries, the von Wurz family appears to have had an immediate relationship to the Empire as seen by the fact that the emperor himself sealed the document in 1069 transferring what was once the family’s allodium into the possession of the bishop of Bamberg. One of the earliest references to specific members of the family is 'Cunradus de Wourz' in 1219.[4] He and his relatives are mentioned in a lawsuit over land and payments brought against him by Abbot Hermann of the Waldsassen Monastery. Once again, a member of the imperial court intercedes personally, as King Friedrich II rules in favor of the monastery and forbids the von Wurz family from attacking the people of the monastery by judicial duel (gerichtszweikampf).

In the service to the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg

[edit]It is difficult to ascertain whether it was due to a weakening stance with the Empire or the imperial preference for the monasteries, but it is clear that the von Wurz family began to distance themselves from the Empire and more closely associate themselves with the regional power structures, namely the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg. In 1252, Heinricus et Conradus de Wrz are listed as witnesses for Friedrich and Gebhart, the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg, at Falkenberg Castle. The service to the landgraves soon became a family affair, as it can be seen that in addition to Heinricus and Conradus, eventually also Gotfridus de Wurz, Gotfridus von Wurz, Albertus von Wurz, Lewe der Wurzer, Hans der Wurzer, Konrad der Wurzer and Ulrich Wurtzer are listed as witnesses for or having affiliations with the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg on numerous occasions:

- 1275: Gotfridus de Wurz is listed as a witness in an arbitration between the Landgrave Gebhard's servant Heinrich von Trautenberg and the Waldsassen Abbey.[5]: 109

- 1277: Gotfridus de Wurz is listed as a witness for Gebhard, Landgrave of Leuchtenberg, in a property sale between Gottfried vom Teich and the Waldsassen Abbey. In this instance, Gotfridus is listed as milites or knight.[5]: 117

- 1279: Gotfridus de Wurze is listed as a witness for Friedrich and Gebhard, Landgraves of Leuchtenberg as they transfer several properties as a gift from Ulrich von Pfrimbt to the Waldsassen Abbey.[5]: 118

- 1279: Gotfrid von Wurz is listed a second time as miles with Gebhard and Friedrich, Langraves of Leuchtenberg. In this instance, Gotfrid's two sons, Albert and Gotfrid, are present.[5]: 122

- 1283: Gotfridus von Wurz is listed as a witness for Heinrich, Landgrave of Leuchtenberg, as he transfers fiefs to Bishop Reimboto von Eystetten. In this document Gotfrid is listed along with several members of the Teutonic Order: Brother Hermannus, Brother Heinricus, Brother Franko, Brother H. de Monecheruthe, Brother Chunradus de Plawe, Brother Albertus Heckil.[5]: 130

- 1291: Gottfried von Wurz is listed as a witness for Gebhard, Landgrave of Leuchtenberg, as he pledges Falkenberg Castle to the Waldsassen Abbey.[5]: 159

- 13th Century: Gottfried von Wurz is listed as a witness in a charter for Ronung von Cammerstein as he gives property to the St. Katharinen Hospital.[citation needed]

On 14 March 1347 the Wurzers are listed in a dispute with the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg over fishing waters. In this same document, the Wurzers are also seen to be in a disagreement with the Steiners, and are ordered to resolve the issue in front of their officials or whomever they choose to do so. [citation needed]

At the apex of the influence of the family, Lewe (also Leo or Leb) der Wurzer states in a document that his dwelling in Hag, which he received as a fief, is an open house for Ulrich and Johann, Landgraves of Leuchtenberg. In 1360, in Nuremberg, Emperor Charles IV as King of Bohemia, on behalf of Ulrich Drezwitzer, gives Leben Wurzer and the heirs of Ulrich's daughter, the wilderness of Albern as a fief.[6] Additionally, Leo Wurzer is listed in the following documents:

- 1364: Leo (Wurzer) is listed as the Vicar of St. Johann in Regensburg and the Supreme Brotherhood Master (Teutonic Order) in a document along with other members of the Teutonic Order.[7] Leo was also a member of the Cathedral Chapter of St. Emmeram in Regensburg.

- 1366: Lebe von Stornstein (Wurzer) is listed as a witness for Hanyk von Knoblauchsdorf, Supreme Captain of the Holy Roman Emperor, in a dispute between the villagers of Etzreut and the Waldsassen Monastery.[8]

- 1372: Lew der Wurzer is listed as the pfleger (caretaker) of Donaustauf Castle and a witness of a property sale between Chonrat der Chrn zu Tomstauff (Donaustauf) and Hartwig den Fischer Burger.

- 1373: Leben den Wurzer is listed as a witness for Konrad der Prukker von Schwabelweis, as he announces that he has been awarded with the wine office by Abbot Alto zu St. Emmeram.[8]

- 1380: Leo v. W. listed as a witness in Rothenburg (Weissbecker).[9]

Other Lineages

[edit]In addition to the main family branch which resided at Wurz, the following are related lineages who maintained residency away from Wurz:

Stornstein Line

[edit]- 1240: Reinhardus de Wrtze is listed in the Urbarium Vicedominatus Lengenuelt as having purchased several fields and an estate in Sitzmannsdorf and a mill-house below the Stornstein Castle.[10]

- 1368: Ulrich Wurtzer is listed in the Bohemian Salbuch (urbarium) as having properties in Horungsberg, Rathawe and Eschenbach. In this urbarium, Ulrich Wurtzer is listed in association with the Stornstein castle along with three other nobles listed as castle guardians (burghüter): Ulrich Jacob, the Pleysteiner and the Eppenreuter. In the fief book 'Das altest Leuchtenberg Lehenbuch', a Wurczer zum Storstein (Stornstein) is listed as one of the "hereditary knights and servants" of the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg, presumably referring to Ulrich Wurtzer.[11]

Rupprechtsreut Line

[edit]- Late-1300s: According to 'Die alteren Mendel von Steinfels', Hans von Wurtz zu Ruprechtsreut, son of Leo Wurzer von Wurz, sold the Hammer Steinfels in 1415 to Hans Mendel. In 1429, Hans Mendel gave the Hammer Steinfels to his son Erhard Mendel. Hans Wurtz's daughter, Utta Wurzer von Wurz, married the knight Erhard Mendel. In addition to the Hammer Steinfels, Erhard received the Forsthube of Ruprechtsreut and the Lintach from his father-in-law, Hans Wurtz. Hans Wurtz is listed as the last of his lineage and is granted permission by Emperor Friedrich III in 1444 to transfer his coat of arms to his grandsons, Hans and Wilhelm Mendel. On 7 June 1454 Hans Wurtz’s son-in-law Erhard Mendel was accepted by the emperor to compete in the tournament and given the title "Mendel von Steinfels". Knight Erhard Mendel von Steinfels would go on to have another son, Christoph, who would become the Bishop of Chiemsee.[12][13]

- 1500s: Hans Wurzer zu Rupersreuth is listed in the following report of the Hofgericht and Parkstein Lorship: "Every two months you may have a district court in Parkstein that has a district judge of lordship, with the following noblemen in the lordship sitting together, these are the following lords, Georg Zenger zu Rothenstadt, Otto Schongraser zu Mospurg, Hans Rackendorfer zu Ullersreut, Hans Wurzer zu Rupprechtsreut, Konrad Erbeck zu Parckstein, Hans Gleissenthaler zu Teltsch, Ulrich Gleissenthaler Burghutter, Hans Lamprecht zu Kalmreut und zu Mairhof and Hans Eteldorfer zum Parkstein, all nine are of the nobility”.[12][13]

Kemnath Line

[edit]- 1373: Hans der Chemnater (Wurzer) is listed as having sealed a document as the judge in the Vorstadt of Regensburg.[7]

- 1374: Hans Wurzzer zu Kemaden is listed as a witness and guarantor in a land sale between Katharina Pernsteiner and Fritz von Redwitz.[14]

- 1377: Hans des Chemenatars (Wurzer) is listed as part of a lawsuit between himself and Cholhoch den Hofar, Hans des Drubenpechks von Nittenenau and Diethochs des Hofar vom Drachenstein.[7]

- 1381: Chunrat der Chemnatar (Wurzer), as the pfleger of Rietenburch, seals a document in which Chunrat der Holzhawsar von Ottling and Fridrich Mawrar sell their property of Vorchhaim to the municipality of Honhaim.[7]

Kaimling Line

[edit]- 1386: Konrad der Wurzer zu Kaimling seals a document for Colonel Gorzen, der Waldauer zu Waldau, his brother Heinrich der Waldauer zu Waldau and Heinrich der Trenk.

- 1396: Konrad der Wurzer zu Kaimling is listed as declaring his last will and testament before pastors Hanns Redwizer u Aydldorf and Hanns zu Kozendorf, the Leuchtenberg judge Hanns den Kozenn, and Otten Engelshofer. In his will, he states that his landlady and his children should stay together as long as they want, but if his landlady doesn't want to stay with the children, then his children should give her 200 guilders and half of the household effects. If she prefers to stay with the children she should receive 100 guilders. His daughter, the Waldauer, is to give him a proper burial, as befits his rank. His son is to receive the fiefdom, i.e. the entire inheritance. In his will, Konrad provides a list of succession. In the event of his son's death, his sister, the Drezwitzer, is to inherit the property. Should his sister die, Hanslein der Wurzer von Wurz should inherit the property. The fiefs that Konrad has from the Waldau family are to be given to his cousin Hansen Seybotz's son Hanslein. Then a pound pfennig is to be donated to his estate in Trauschendorf near Roggenstein for a “perpetual anniversary". As were Gotfrid and Leo before him, Konrad was also associated with the Teutonic Order.[13]

Conclusion

[edit]The 14th and 15th centuries were a time of turmoil for the lower nobility. With the advent of the use of gunpowder, pikesmen and professional armies in Europe, the demographic fallout from the Black Death, the Great Famine of 1315-1317 and the subsequent rise of the merchant class, many of the medieval knightly families struggled to maintain their wealth and position. Some of the noble associates of the Wurzer family resorted to becoming robber barons (i.e. the Sparneckers), as punishment for which many of them lost their titles and property. The main lineage of the Wurzer family died out with Hans von Wurtz zu Ruprechtsreut, and at the same time other family lines began to experience financial and legal difficulties:

- A document dated 1 January 1413 states in a letter that Hanns der Wurzer, son of Peter des Wurzer von Chraiezpach, was being imprisoned at Kollnburg castle, because he had beaten and threatened the nobleman and marschall Konrad den Nusperger zu Kolmberg. In this letter, he also states that because of his imprisonment his friends and his father were speaking for him and that he had lost all of his possessions.

- A document dated 6 February 1414 states that Ulrich Cleistentaler zu Dietersdorf relieves Johann, the Landgrave of Leuchtenberg, Count zu Hals and his cousins Leutpold and Georg, the Landgraves of Leuchtenberg, of all of the mortgages that the Landgrave Johann held when he died. Due to the fact that Landgrave Albrecht died, and his cousin Landgrave Ulrich died, Landgraves Johann and Leutpold were obliged to repay these debts. However, Ulrich Cleistentaler declared that all of the promissory notes were invalid, with the exception of the debt notes that he had from the Landgrave for Konrad zu Weissenstein Nothaft, Hans Ramsperger zu Waldmunchen and Hans den Wurzer.

From the 15th century onward, members of the family became incorporated into the landed gentry, and by the mid-1600s descendants of the family show up in local baptismal records as farmers. According to the Häuserbücher (House books) of Helmut Reis, members of the Wurzer family can be found living in the villages in and around Wurz and Leuchtenberg from the 1500s up until current times.[15]

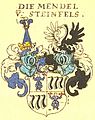

Coat of arms

[edit]- Coat of arms: Three (2/1) black 'uttenschwalbe' (possibly a cormorant or stork) charges in silver. Helmet: expanding black 'uttenschwalbe' with outspread wings. Markings: black, silver.[1] In 9 September 1444 the Wurzer coat of arms is described as follows: "...having a white shield and in it 3 black uttenschwalbe charges, red beak...and a helmet, adorned with a white and black lambrequin and from it a black uttenschwalbe charge between 2 black wings with a red beak...".[12]

- The Wurzer coat of arms was later incorporated into the coat of arms of the Mendel von Steinfels family. A document from Emperor Maximilian I, dated 29 March 1506 in Neustadt, states that the last von Wurtz "with the permission of our dear lord and father, the Roman Emperor, while his dearest was still Roman king (i.e. before 1452) yields his hereditary coat of arms, also all of his belongings, fiefs and property on the sons of his daughter, Hans and Wilhelm Mendel von Steinfels.[1]" "His dearest" refers to King Friedrich III. The "last von Wurtz" refers to Hans von Wurz zu Ruprechtsreut. His daughter is Utta Wurzer von Wurz, wife of Knight Erhard Mendel von Steinfels, and mother of Hans and Wilhelm Mendel von Steinfels.

-

Wax Seal, Leo Wurtzer[16]

-

Stone memorial at Wurz

-

Wurzer coat of arms combined with that of Mendel v. Steinfels

Possessions (fiefs)

[edit]- Schonficht Castle and village (1380), sold by Leo Wurzer to Andreas Zenger (1387)[17]

Fiefs listed in the Monumenta Boica: Urbarium Vicedominatus Lengenuelt[18]:

- Sitzmannsdorf (fields, a court) and a mill below the castle, presumably Stornstein (Reinhardus de Wrtz, 1240)

Fiefs listed in the Bohmische Salbuchlein:[19]

- Iron hammer mill at Hammerharlesberg (Ulrich Wurtzer, 1368)

- Roschau, a wilderness farm (hofe) (Ulrich Wurtzer, 1368)

- Eschenbach, 20 acht habern, 21 morning fields, 5 tagwerch wisma (Ulrich Wurtzer, 1368)

Fiefs listed in The Oldest Leuchtenberger Fiefbook[20]

- Wurz near Neustadt an der Waldnaab (Wurczer, forename missing. Possibly Hans von Wurz zu Ruprechtsreut)

- Haag (unknown), possibly between Creussen and Bayreuth (Wurczer, forename missing. Possibly Hans von Wurz zu Ruprechtsreut)

- Harbe, a wilderness (Wurczer, forename missing. Possibly Hans von Wurz zu Ruprechtsreut)

- Mitteldorf near Wurz (Leo Wurczer)

- Rotzendorf near Wurz (Leo Wurczer)

- Gossenreuth near Wildenreuth (Leo Wurczer)

- Feretrichsenreut (unknown) (Leo Wurczer)

- Galprechtsholz near Schonficht (Leo Wurczer)

- Castle hut (burghut) in Stornstein (Wurczer zum Stornstein, forename missing. Possibly Ulrich Wurtzer)

- Kaimling near Vohenstrauss (Chunrad Wurczer)

- Maisthof near Luhe (Hanns Wurczer)

- Goldbrunn near Waldthurn (Hanns Wurczer)

Prominent members of the family

[edit]- Conradus de Wourz, nobleman (1219,[21] 1252[22])

- Reinhardus de Wurze, burgmann, Stornstein (1240[23])

- Heinricus de Wurz, nobleman (1252[22])

- Gotfridus de Wurz, knight (miles) (1275,[5] 1277,[5] 1279,[5] 1283,[5] 1291[5])

- Albertus de Wurz, knight (1279[5])

- Gotfridus de Wurz, knight (1279[5])

- Ulrich der Wurzer, burgmann, Stornstein (1313, 1368,[11] 1400s[20])

- Lewe (Leo/Leb) der Wurzer, knight, Pfleger of Donaustauf Castle, Vicar of St. Johann in Regensburg, Supreme Brotherhood Master of the Teutonic Order (1358, 1360,[24] 1364,[7] 1366,[7] 1372, 1373,[7] 1380,[1] 1400s[20])

- Hans von Wurz zu Ruprechtsreut, knight (late-1300s,[12] 1414)

- Utta Wurzer von Wurz (before 1452[1])

- Hans Mendel Gmund, knight[1]

- Wilhelm Mendel von Steinfels, knight[1]

- Hans Wurzer zu Kemaden (Chemnatar), nobleman, judge in the Vorstadt of Regensburg (1373,[7] 1374. 1377[7])

- Chunrat der Chemnatar, nobleman, Pfleger of Rietenburch (1381[7])

- Konrad der Wurzer zu Kaimling, nobleman (1386, 1396, 1400s[20])

- Hanslein der Wurzer von Wurz, nobleman (1396, 1400s[20])

- Peter des Wurzer, nobleman, Chraiezpach (1413)

- Hanns der Wurzer, nobleman (1413)

- Hans Wurzer zu Rupersreuth, nobleman, member of the Parkstein district court (1500s[25])

Notable associates

[edit]

The von Wurz family were directly related to the following families: Waldau, Drezwitzer, Mendel von Steinfels.

The following are listed in documents as witnesses along with members of the von Wurz family:

- King Heinrich IV (1069)

- Bishop Hermann of Bamberg (1069)

- King Friedrich II (1219)

- Duke Otto de Meran (1219, 1252)

- Langraves of Leuchtenberg: Landgrave Gebhard (1219, 1252, 1275, 1279, 1291), Landgrave Friedrich (1219, 1252, 1279), Landgrave Heinrich (1283)

- Maequardus & Heinricus de Trutenberch (Trautenberg) (1252, 1275, 1200s)

- Dymarrus de Clyspental (1252), Gotfrid von Gleissenthal (1279)

- Otto de Zenst (1275, 1277, 1279, 1279, 1283, 1291, 1200s)

- Ulricus de Phrimde (1275, 1277, 1279, 1279, 1291)

- Trutwinus de Redwicz (Redwitz) (1277), Wernherus de Redwitz (1279)

- Rupertus de Libenstein (1279)

- Albertus & Waltherus Nothaff (1279)

- Wolff de Wisstenstein (1279, 1279)

- Heinricus & Gotfridus de Oberndorff (1279)

- Eberhard von Tanhausen (1279)

- Bishop Reimboto of Eichstatt (1283)

- Teutonic Knights (Brothers Hermannus, Heinricus, Franko, H. de Monecheruthe, Chunradus de Plawe, Albertus Heckil) (1283)

- Burggrave Friedrich von Nurnberg (1291)

- Bado de Spareeck (Sparneck) (1283)

- Albertus de Hertenberch (Hertenberg) (1291)

- Emperor Charles IV (1360)

- Count zu Hals (1414)

- Emperor Friedrich III (1444)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Großes und allgemeines Wappenbuch. Bauer & Raspe.

- ^ a b c Schulze, Christoph (1988). Wrzaha Wurz in der nordlichen Oberpfalz (in German). Christoph Schulze.

- ^ Bohmer, Johann Friedrich (2016). Regesta Imperii III. Salisches Haus 1024-1125. Tl. 2: 1056-1125. 3. Abt.: Die Regesten des Kaiserreichs unter Heinrich IV. 1056 (1050) - 1106 (in German). Bohlau Verlag. p. 82. ISBN 978-3412505974.

- ^ 'Regesta imperii. 5,1,1: Die Regesten des Kaiserreichs unter Philipp, Otto IV., Friedrich II., Heinrich (VII.), Conrad IV., Heinrich Raspe, Wilhelm und Richard 1198 - 1272 ; 1, Kaiser und Könige ; [1]', Image 1 of 751 | MDZ (digitale-sammlungen.de)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Gradl, Heinrich (1886). Monumenta Egrana: Denkmäler des Egerlandes als Quellen für dessen Geschichte. 805 - 1322. 1 (in German). Witz.

- ^ Kaiser, Reinhold (1995-08-01). "J. F. Böhmer, Regesta Imperii I. Die Regesten des Kaiserreichs unter den Karolingern 751–918 (926). Abt. 3: Die Regesten des Regnum Italiae und der burgundischen Regna. Teil 1 : Die Karolinger im Regnum Italiae 840–887 (888), bearb. von Herbert Zielinski". Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Germanistische Abteilung. 112 (1): 493–494. doi:10.7767/zrgga.1995.112.1.493. ISSN 2304-4861. S2CID 163731998.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Die Urkunden-Regesten des Kollegiatstiftes U. L. Frau zur alten Kapelle in Regensburg (heimatforschung-regensburg.de)

- ^ a b "Charter DE-StAAm|Waldsassen|447 - Monasterium.net". www.monasterium.net. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ "Verhandlungen des Historischen Vereins für Oberpfalz und Regensburg 33. Band (1878) - heimatforschung-regensburg.de". www.heimatforschung-regensburg.de. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ "'Monumenta Boica. 36,1, Urbarium ducatus Baiuwariae antiquissimum ex anno 1240 c. Urbarium ducatus Baiuwariae posterius ex anno 1280 circ. Urbarium vicedominatus Lengenuelt. 1326' - Viewer | MDZ". www.digitale-sammlungen.de. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ a b "Das "Böhmische Salbüchlein" Kaiser Karls IV. über die nördliche Oberpfalz (1973) - Bayerische Staatsbibliothek". www.osmikon.de. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ a b c d 1223758_DTL2337.pdf (heimatforschung-regensburg.de)

- ^ a b c Wurzer, Josef (2010). Ein tausendjahriges Geschlecht das der Wurzer (in German). Bad Reichenhall: Josef Wurzer.

- ^ "Verhandlungen des Historischen Vereins für Oberpfalz und Regensburg 33. Band (1878) - heimatforschung-regensburg.de". www.heimatforschung-regensburg.de. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ "Häuserbücher von Helmut Reis – GenWiki". wiki-de.genealogy.net. Retrieved 2022-03-30.

- ^ "Charter DE-BayHStA|KURegensburgStEmmeram|000653 - Monasterium.net". www.monasterium.net. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ a b "Burgstall Schönficht", Wikipedia (in German), 2021-10-23, retrieved 2022-03-28

- ^ "'Monumenta Boica. 36,1, Urbarium ducatus Baiuwariae antiquissimum ex anno 1240 c. Urbarium ducatus Baiuwariae posterius ex anno 1280 circ. Urbarium vicedominatus Lengenuelt. 1326' - Viewer | MDZ". www.digitale-sammlungen.de. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ Das "Böhmische Salbüchlein" Kaiser Karls IV. über die nördliche Oberpfalz - BSB-Katalog (bsb-muenchen.de)

- ^ a b c d e 1347451_DTL2112.pdf (heimatforschung-regensburg.de)

- ^ "'Regesta imperii. 5,1,1, Die Regesten des Kaiserreichs unter Philipp, Otto IV., Friedrich II., Heinrich (VII.), Conrad IV., Heinrich Raspe, Wilhelm und Richard 1198 - 1272 ; 1, Kaiser und Könige ; [1]' - Viewer | MDZ". www.digitale-sammlungen.de. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ a b Gradl, Heinrich (1886). Das Egerland: Heimatskunde des Ober-Eger-gebietes (in German). A.E. Witz.

- ^ "'Monumenta Boica. 36,1, Urbarium ducatus Baiuwariae antiquissimum ex anno 1240 c. Urbarium ducatus Baiuwariae posterius ex anno 1280 circ. Urbarium vicedominatus Lengenuelt. 1326' - Viewer | MDZ". www.digitale-sammlungen.de. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ "'Regesta imperii. 8, Die Regesten des Kaiserreichs unter Kaiser Karl IV. 1346 - 1378' - Viewer | MDZ". www.digitale-sammlungen.de. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

- ^ "Verhandlungen des Historischen Vereins für Oberpfalz und Regensburg 92. Band (1951) - heimatforschung-regensburg.de". www.heimatforschung-regensburg.de. Retrieved 2022-03-28.

![Wax Seal, Leo Wurtzer[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Seal_of_Leo_Wurtzer.jpg/119px-Seal_of_Leo_Wurtzer.jpg)